Sample

Shaman

Ulaanbaatar

We have entered a new universe.

The path is so worn and dusty it cannot possibly lead anywhere new. Surely this path has before been trod. But we tread nonetheless, because it is a path that is new to us.

The tent is filthy. In a grotty car park in a ravaged city, it cannot hold anything worth knowing. It cannot be a journey worth following. We enter nonetheless.

Nonetheless. With nothing less or more to be gained. Despite this, we enter.

The central point rises high, and skylight pours in to bathe the space suddenly beautiful in soft rays and diluted shadows.

There’s the spectacle though. A fantastic monster of a beast replete in his regalia, his sewed-on bones and his feathers, his hat topped by a stuffed head, his brocade and his drum. Immersed in his delirious, intoxicated frenzy. He is sweating from his beard and his eyebrows and his cheeks. He pounds his drum with a small cudgel, rings clattering, rings swinging and singing. And he sings, moaning and yelling, filling the space with warnings, dire predictions, and blessings that pour profanely from his ajar jaw, his lisping, gleeching tongue, his ululating throat.

Attendants hand both acolytes and visitors small brass bowls and pour into them milk in which swirl tiny streams of fat and particles foreign to milk. The Westerners perch foolishly on their stools, holding the tiny bowl in the fingers of one hand and grasping a biscuit and two lollies they have been handed in the other, which may or may not have some role in the ensuing performance.

They glance at one another. Suddenly a couple of tablespoons of milk is a challenge they may not be able to meet. Will they have to drink it?

There are five women around the altar. Three aged women hard at work. One beating a drum in the background, and one organising and preparing, and one doing. Then two younger women, one dancing, dancing, dancing, dancing. She falls to her knees, tired, but at a commanding half-grunt half-shriek from the Shaman she rises again and continues.

Every surface of the ger is decorated. Stuffed eagles and owls appear at various points on the rear wall, dozens of tiny candles light the altars, nearly every surface is wooden, and every wooden surface is painted, icons hang about the walls, light streams from above, carpets, both rich and pedestrian, lay on the broken concrete floor, the altars are old cupboards with thrills of paintwork dancing over them, and the most insistent motive is horse – horse head sculptures, horse adornments on instruments, horse figurines in the cupboards, paintings.

The volume increases. Chanting but not chanting, singing but not in tune. It is mad, insane, exciting. The Shaman pounds his drum and sings, cacophonic, monotonous, spittle-laden, loud, LOUD! Old toothless beside him plays harmonics and off-notes on two strings. Repetitive without rhythm. The Shaman leaps to his feet, screaming Mongolian screams, stepping fully into the space. Whirling. Belting out his complete understandings of everything and everything. He jumps over and again, landing with earth-shaking thuds only to lift his huge frame into the air and thud again. His legs are solid, large, but he is massive. He stops before me and showers me with spit, his huge belly thrusting litres of air through his system and pours into the huge tent power, power, power. He belts the drum. He thumps it over and again. He wails, moans, moves on. He beats up a frenzy, howling his prayers to wake up the gods and let the bastards know we are there. He collapses onto his throne. Sweat washes down his face.

On the far side of the tent the followers sway side to side, their clasped hands swing in horizontal circles, eyes closed, in the moment. Behind me a couple of men do the same. The eight Westerners look nervous. One of the teenagers is more explicit. He mouths silently to a friend across the space – “W T F ?”

A second young woman, beautiful of movement and wrapped in ornate cloth and veiling headdress, attends the first who has momentarily collapsed, removes her headgear to reveal a bald scalp and replaces the first hat with a second, greater, more dazzling, more feathers, more braids trailing down to her knees, more shapes, more colours. The attendant supports the newly head-dressed woman to her feet and she stumbles again into dance.

Now tripping here and there, awkward in her Levi Space shoes, she drags herself around the ger, the intention is to leap but it is a stumble, the intention is to twirl, but it is a twist. The Shaman yells an order over the singing. Obediently the second attendant jumps to dance. She is less experienced but her enthusiasm is inspiring. She throws herself into the air. Her knees are high, her arms flail, her head is thrown backwards and forwards. It is a mosh pit of one in a cloth cathedral. Her many long, coloured braids fly out behind her, catching and clattering against the rear of the antique electric fan juddering spastically on its stand. Even the fan joins in the dance.

Just as it couldn’t get any more wonderful, strange or bizarre, one of the assistants drags through the ornate tent door a chain, to which is attached a fully fledged, flapping, magnificent, majestic, eagle.

The gender segregated audience gapes. The eagle is as surprised as any of us. It eyes us warily.

The galloping Shaman hoiks his bulk again around the ger. He throws himself at the sky and ground. He whacks the drum at the eagle. The eagle flaps and darts away from the banging, suddenly in the air travelling to the end of its chain where it stops abruptly, dropping one unbelievably massive, outstretched wing onto the head of an astonished Welsh traveller who shrieks and drops her biscuits and milk as she pulls away.

The faithful are completely into it all. The Westerners are horrified at the treatment of the eagle, getting troubled about how long this thing is going on for, and still worried about the milk. My friends Kalista and Dominique, sitting on the other-gender side of the performance, stare entranced. They don’t know that the women around them have their eyes closed, in trance. The second young woman, the attendant, the beautiful one with the ornate gear and great moves flails past me one more time, her embroidered minute dreadlocks and plaits fly up from her face. I catch a glimpse of an eye, electric beneath the ornamentation.

And at that point my universe turns upside-down.

I know the dancer.

A decade or so has passed, sure, but it’s her.

I know the dancer.

I last saw her on Lygon Street, Carlton, when we said goodbye because she was heading to America on some mad jaunt. She was my girlfriend at the time.

It’s Anne.

I am desperate to contact her, to connect with her. She was so brilliant, so funny, so eternally strange. She was so fluid in her connection to time and place that if ever I suddenly turned up on her doorstep and said, ‘Let’s go to a movie / meal / bowling / scuba diving / caving / parade / have sex / do macramé / learn Polish …’ she would simply acquiesce, but that never meant she didn’t have a will of her own, or power, or intention. It just seemed that in my orbit, she was completely open to new directions.

The drumming has sped up again and Anne is still dancing. I am in love with her, obviously. I am in love! Still! It has been ten years, and she is now a madly twirling bejewelled dancer, in Mongolia. How bizarre!

The noise is increasing. The fury is increasing. It can’t possibly go on. It can’t possibly get louder. Not accelerate any more. It is too much! Too much! Too –

With a final shriek to open the heavens and drive demons from our souls, the Shaman collapses to the ground, as do the drummers, the string player, the dancers, and Anne. Even the eagle is now still, as though exhausted. Perhaps it has done its thing. There is the sound of heaving chests and lungs, everyone is starved of oxygen. The stench is intense. There is no air left.

Everyone has run a marathon. It is the end of the show, and what a show it was.

I try to move forward – Anne has to see me. But already she is leaving through the back of the ger past the stalls and the ornaments and the rickety electric fan.

I leap over people praying and try to get to her, but recumbent musicians catch my arms and hold me back – clearly Westerners can’t just chase the dancing girls. I try to explain, but my Mongolian is limited to ‘Neg _ hand ve?’ and ‘Utsik penno?’ – and even if they could find a pen to lend me in this madly over-decorated tent, I wouldn’t be able to explain any better what it is that I want – I want Anne.

‘Anne!’ I scream. ‘Anne Marie Campbell! Anne!’

But her delirium must be complete. Her disconnect sufficient. For I cannot contact her.

I wait for hours outside. My friends are tired and becoming impatient. ‘Bugger off,’ I tell them. ‘I’ll catch you in a week or so. I’m not leaving here until I find her.’

But I do not find her.

And, despite the best efforts of experts and the internet, have not seen her since.

And the only image I have of her now is the one in my head, a lightning glimpse of ornate make up and complex hair, in a whirl of colour and smell, in a tent, in Mongolia.

IP (Interactive Publications Pty Ltd)

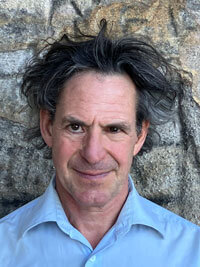

‘I enjoyed this so much – this man writes beautifully.’

– Phillip Adams

IP (Interactive Publications Pty Ltd)

‘Literary, beautifully written, meticulously plotted and inventively surprising.’

– Kerry Greenwood

IP (Interactive Publications Pty Ltd)

‘A little frightening, sometimes immensely funny, and consistently beautiful writing; these wonderful, sensual tales of love, union, desire and transformation throw open the notion of travel and what it means to come alive in a strange landscape.’

– Magdalena Ball, The Compulsive Reader